As Andrew Ross Sorkin's 1929 masterfully unravels the narrative of the Roaring Twenties, the reader is transported to an era of boundless optimism, where the "new era" of permanent prosperity was the gospel of the day. The recent release of this book has reignited a century-old anxiety: Could it happen again? And if it did, would we face another Great Depression?

The Crash of 1929 remains the ultimate cautionary tale of modern capitalism. It was not merely a financial event; it was a cultural trauma that redefined the relationship between the state, the market, and the citizen. However, while human psychology—driven by fear and greed—remains constant, the machinery of our financial system has undergone radical reconstruction.

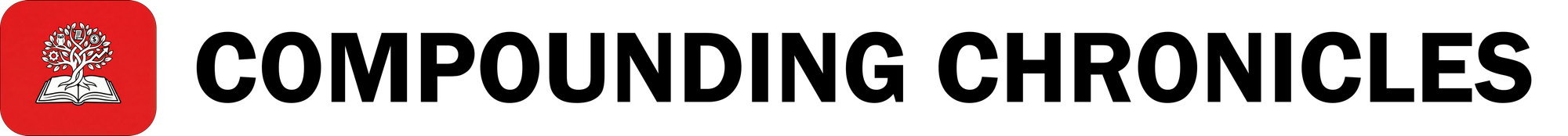

This article explores the cataclysm of 1929, the subsequent economic winter, and crucially, why the modern financial architecture makes a repeat of the Great Depression’s severity highly unlikely. We will examine the stark differences in stock ownership, regulatory bodies like the SEC, the strategy of the Federal Reserve, and the safety nets that simply did not exist in October 1929.

Part I: The Crash and the Great Depression

The Euphoria Before the Fall

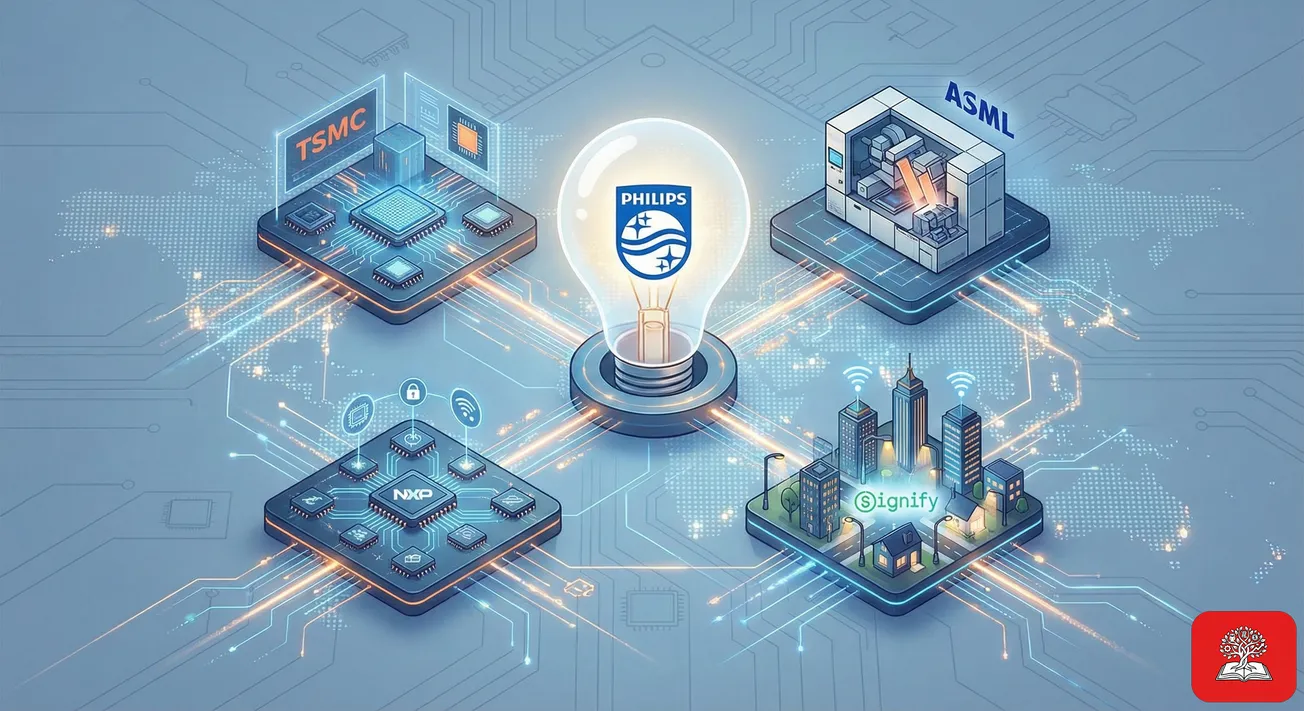

To understand the crash, one must understand the height from which the market fell. The 1920s were characterized by the mass adoption of revolutionary technologies: the radio, the automobile, and electrification. Stocks like RCA (Radio Corporation of America) were the Nvidias and Teslas of their day, soaring on the promise of a connected future.

By 1929, the market had decoupled from reality. The Dow Jones Industrial Average had increased six-fold from 1921 to 1929. This bull market was fueled by "call money"—loans from corporations and banks to brokers, who then lent it to investors. The mood was electric; the conviction was that the old cycles of boom and bust had been conquered by the Federal Reserve and modern industrial efficiency.

The Week That Changed the World

The crash was not a single day, but a rolling collapse. It began in earnest on Black Thursday, October 24, 1929. The market opened with a gap down, and panic set in. By noon, the ticker tape was hours behind. In a dramatic scene often recounted (and detailed in Sorkin’s work), a consortium of bankers led by Thomas W. Lamont of J.P. Morgan met across the street from the NYSE. They pooled resources to buy blue-chip stocks like U.S. Steel at above-market prices, attempting to put a floor under the market. It worked—temporarily.

The relief lasted only until the following week. On Black Monday (October 28) and Black Tuesday (October 29), the selling resumed with ferocious intensity. The bankers did not step in a second time. On Black Tuesday alone, 16 million shares were traded—a record that stood for nearly 40 years. By mid-November, the market had lost half its value.

The Descent into Depression

The crash itself did not cause the Great Depression; the policy response did. Following the crash, the economy entered a liquidity trap. Banks, terrified of runs, stopped lending. Consumers, terrified of unemployment, stopped spending.

Between 1929 and 1932:

- GDP collapsed by nearly 30% (vs. roughly 4% during the 2008 Great Recession).

- Unemployment soared to 25%.

- Deflation set in, with prices falling by 30%, increasing the real burden of debt for farmers and homeowners.

- Bank Failures: Over 9,000 banks failed during the 1930s. When a bank failed, depositors lost everything.

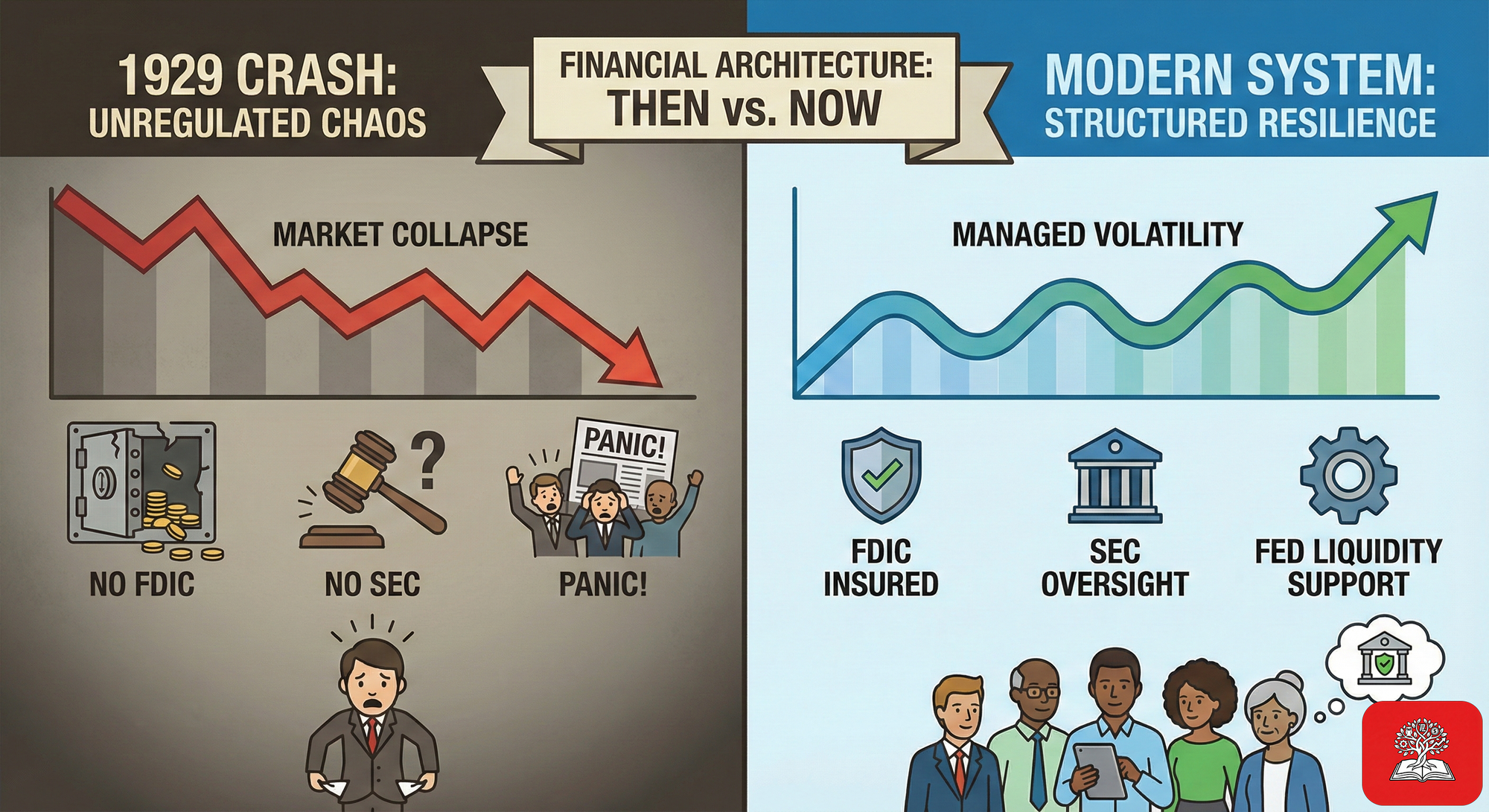

Part II: The Structural Chasm—1929 vs. Today

While the charts of 1929 and modern bubbles often look frighteningly similar, the underlying structures of the market and the economy are fundamentally different.

1. Market Participation: The Few vs. The Many

- 1929: Despite the stories of shoeshine boys giving stock tips, the actual ownership of stocks was incredibly concentrated. Estimates suggest that only 1.5 million to 3 million Americans owned stock in 1929, out of a population of roughly 120 million. This represents approximately 1-2.5% of the population. The crash destroyed the wealth of the elite and the upper middle class, but it damaged the average American primarily through the subsequent bank failures and job losses, not direct portfolio losses.

- Today: The democratization of finance has changed the stakes. According to recent Gallup data (2023-2025), approximately 61% of Americans own stock, either directly or through 401(k)s and pension funds. While this makes a crash more broadly felt today, it also means the market is deeper and more liquid. In 1929, when the few wealthy players wanted to sell, there was literally no one on the other side of the trade. Today, institutional capital, passive index funds, and retail investors create a more diverse (though still volatile) liquidity pool.

2. The Wild West vs. The Watchdogs (The SEC)

- 1929: The SEC did not exist. The stock market was essentially self-regulated by the exchange, which was run like a private club.

- Insider Trading: Was legal and rampant. "Pools" of wealthy investors would conspire to inflate the price of a stock (pump) and then sell it to unsuspecting public investors (dump). Sorkin’s book details the mechanics of these pools.

- Financial Reporting: Companies were under no federal obligation to publish audited financial statements. Investors often bought stocks based on rumors and dividends, with zero insight into the company's actual balance sheet.

- Today: The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), established by the Securities Exchange Act of 1934.

- Transparency: Public companies must file quarterly, audited reports (e.g. 10-Qs).

- Market Surveillance: Sophisticated algorithms monitor for manipulation and insider trading. While not perfect, the blatant "pools" of the 1920s are impossible to execute today without immediate detection.

- Circuit Breakers: Following the 1987 crash, exchanges introduced circuit breakers. If the S&P 500 drops 7%, 13%, or 20%, trading is halted. This pauses the panic, allowing investors to digest information, a mechanism that would have stopped the freefall on Black Tuesday.

3. Leverage: The Lethal Multiplier

- 1929: The defining feature of the 1929 bubble was unregulated leverage. Investors could buy stock with 10% down (10:1 leverage). If you had $100, you could buy $1,000 worth of stock.

- The Consequence: If the stock dropped just 10%, your equity was wiped out, triggering an immediate "margin call." The broker would sell your stock instantly to recover the loan. This created a domino effect: selling begat selling.

- Today: Under Federal Reserve Regulation T, the initial margin requirement is set at 50%. While derivatives and options allow for higher effective leverage, the baseline for the average stock investor is far more conservative. This cushion prevents the cascading "forced liquidation" cycles that defined 1929.

4. The Federal Reserve: From Villain to Savior

This is arguably the single biggest difference.

- 1929 Strategy (The Real Bills Doctrine): The Federal Reserve of 1929, led by a disjointed board, made catastrophic errors.

- Tightening into Weakness: As the crash unfolded, the Fed focused on defending the Gold Standard and curbing "speculation." They kept interest rates relatively high and, crucially, allowed the money supply to contract by nearly a third.

- Laissez-Faire Banking: They viewed bank failures as a necessary "cleansing" of bad management. They did not act as a lender of last resort.

- Today’s Strategy: Modern central banking, informed heavily by the lessons of 1929, operates on opposite principles.

- Liquidity Injection: In a crisis (like 2008 or 2020), the Fed floods the system with liquidity (Quantitative Easing). They slash interest rates to zero to encourage lending.

- Lender of Last Resort: The Fed explicitly guarantees the liquidity of the banking system to prevent the credit freeze that causes depressions.

5. The Safety Net: FDIC and Social Security

- 1929: When a bank failed in 1929, the money was simply gone. There was no insurance. This caused the "paradox of thrift": people hoarded cash under mattresses, pulling it out of the economy, which caused more banks to fail. Furthermore, there was no unemployment insurance or Social Security. Losing a job meant immediate destitution.

- Today: The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) insures deposits up to $250,000. Even if a bank fails (as SVB did in 2023), depositors do not lose their money. This prevents the bank runs that decimated the 1930s economy. Additionally, automatic stabilizers like unemployment benefits and food assistance put a floor under consumer demand, preventing the economy from spiraling into a total void.

Part III: Why a "Depression" is Unlikely Today

The term "Depression" implies a long-term, structural collapse of economic activity, lasting years. A "Recession" is a normal part of the business cycle. While we will certainly face recessions, a 1929-style Depression is unlikely for three key reasons:

- Fiat Currency vs. Gold Standard: In 1929, the U.S. was tied to gold. The government could not simply "print" money to stimulate the economy without running out of gold reserves. Today, with a fiat currency, the Federal Reserve and Treasury have theoretically unlimited firepower to stimulate nominal demand. They can debase the currency to prevent deflation.

- Institutional Memory: We know what happened. In 2008 and 2020, policymakers explicitly referenced 1929 as the scenario to avoid at all costs. The "overreaction" of stimulus we see in modern crises is a direct result of trying to avoid the "under-reaction" of 1930-1932.

- The Service Economy: The 1929 economy was heavily industrial and agricultural. These sectors are capital-intensive and slow to turn. Today’s economy is service and information-based, which is generally more resilient and adaptable to shocks.

Conclusion: The Human Variable

Andrew Ross Sorkin’s 1929 reminds us that while the mechanics of finance change, the software of the human brain does not. We are still prone to herding, confirmation bias, and panic. A crash can happen. Markets will correct.

However, the "Depression" was a failure of government and banking architecture, not just a failure of stock prices. We have built firewalls—the SEC, the FDIC, the active Fed—that make the burning down of the entire house far less probable. We may lose money in the market, but we are unlikely to lose the economy itself.

References

- Book: "1929" by Andrew Ross Sorkin (link)

In my opinion, for the best experience, you should listen to the audiobook, as Andrew Ross Sorkin narrates it himself.