For nearly six decades, Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger formed the most successful investment partnership in history. Their collaboration transformed a failing New England textile mill into a big conglomerate, defied the efficient market hypothesis, and created a cult-like following of shareholders who flocked to Omaha annually to hear them speak.

To the uninitiated, they appeared to be two peas in a pod: two elderly, bespectacled Midwesterners who drank Coke, ate peanut brittle, and preached the virtues of value investing. However, to view them as identical is not entirely correct and misses the magic of their partnership. It was the friction between their differences, the bedrock of their similarities, and the compounding power of their synergies that created the anomaly known as Berkshire Hathaway.

This article explores the three biggest differences, three biggest similarities, and three biggest synergies between Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger, analyzing how this unique dynamic duo conquered the financial world.

Part I: The Three Biggest Differences

While their destination was often the same, the maps Buffett and Munger used to navigate the world were distinct. These differences were not points of contention but rather complementary forces that expanded Berkshire’s potential.

1. The Graham Disciple vs. The Quality Architect

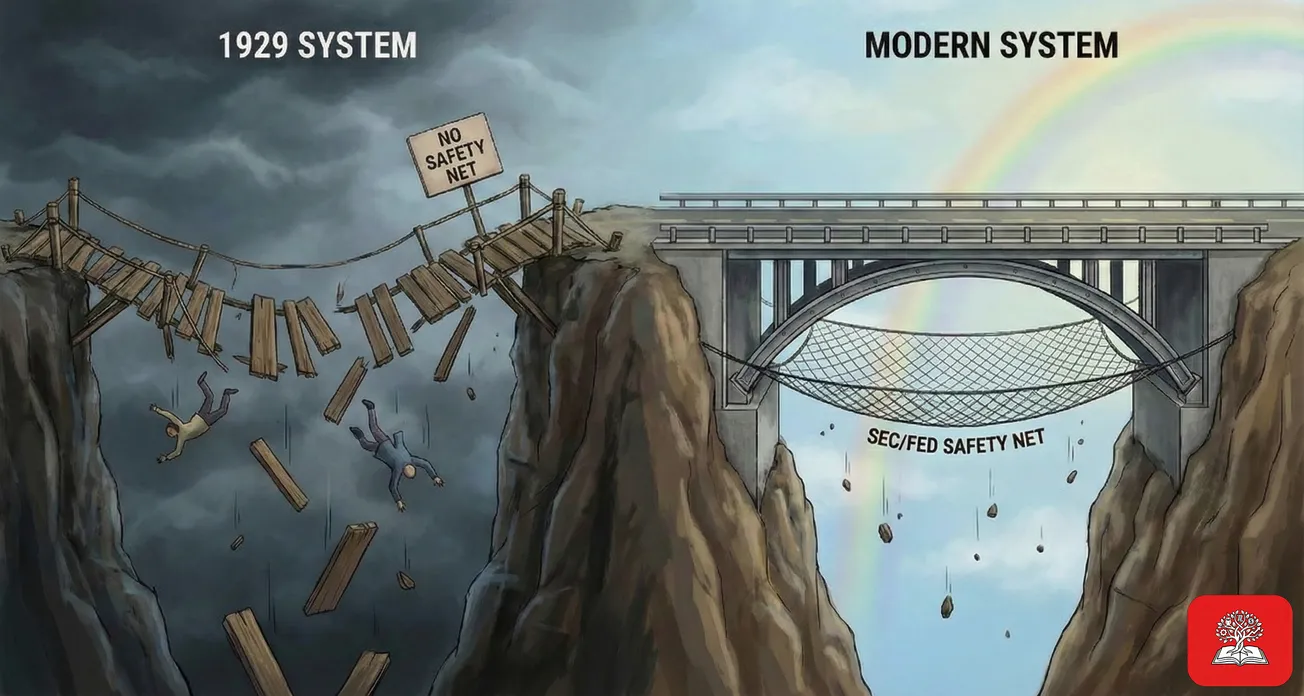

The most profound difference lay in their foundational investment philosophies. Warren Buffett began his career as a devout disciple of Benjamin Graham, the father of value investing. Graham’s philosophy was born out of the trauma of the Great Depression; it was defensive, quantitative, and pessimistic. Buffett was trained to look for "cigar butts"—companies that were statistically cheap, often trading below their net working capital. These were poor businesses, but if bought cheaply enough, they offered a "free puff" of profit before being discarded.

For the first two decades of his career, Buffett hunted for these bargains. He didn't care about the quality of the business, the brand, or the management. If the math worked—if he could buy a dollar for fifty cents—he bought it.

Charlie Munger, however, never fully bought into the "cigar butt" approach. A lawyer by training and an admirer of Phillip Fisher, Munger was less interested in a bargain price and more interested in business quality. Munger understood that time is the enemy of the mediocre business but the friend of the great business. He argued that buying a fair business at a wonderful price (Buffett’s approach) was inferior to buying a wonderful business at a fair price (Munger’s approach).

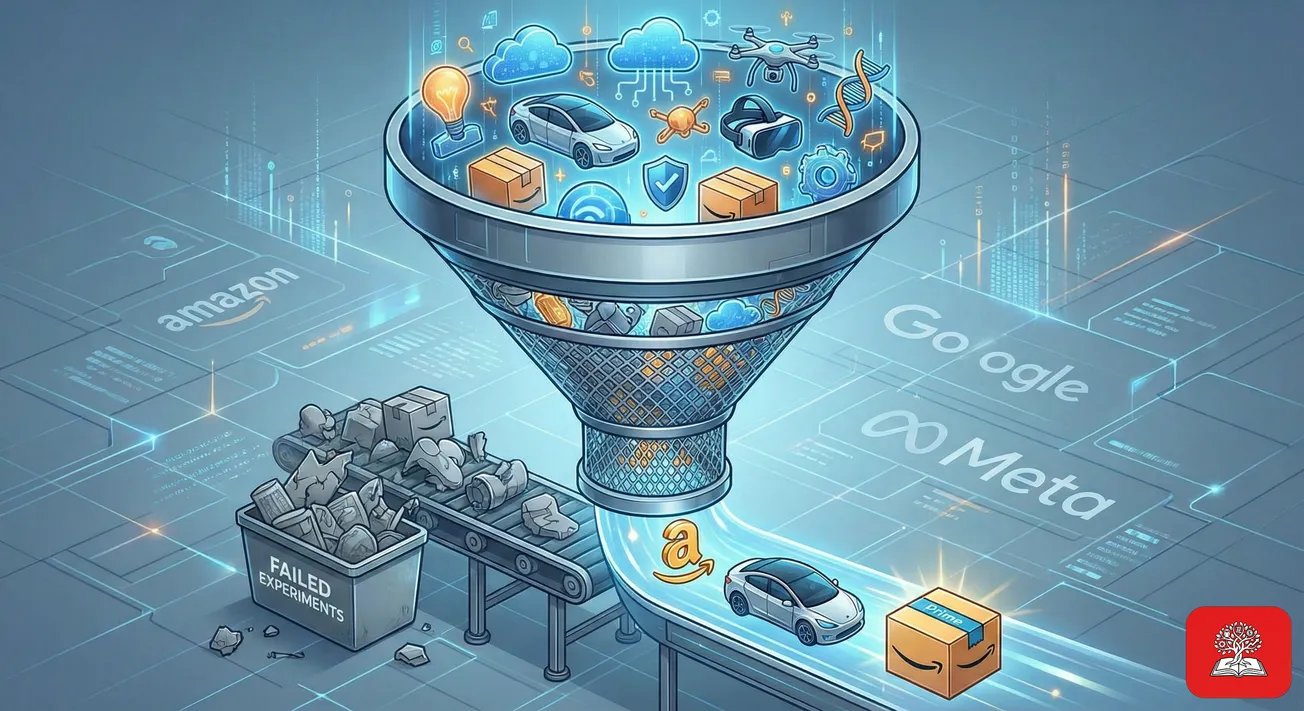

Munger realized that "cigar butt" investing was not scalable. You had to constantly find new bargains, sell them, and pay taxes. A great business, however, could be held forever, allowing capital to compound tax-free. While Buffett was sifting through the trash for discarded value, Munger was looking for castles with unbreachable moats. This philosophical divergence was the primary engine of their evolution, a point we will explore in the "Synergies" section.

2. Deep Specialization vs. The Latticework of Mental Models

Warren Buffett is a specialist. His focus is singular and laser-sharp. He has spent his entire life on studying businesses, accounting, and capital allocation. He famously claimed to read 500 pages of annual reports every day. His genius lies in his ability to look at a financial statement and almost instantly visualize the economic engine of the company. He is a processing machine dedicated to one specific domain: business valuation.

Charlie Munger, conversely, was a generalist—a polymath who believed that specialized knowledge was dangerous. He famously mocked the "man with a hammer" syndrome: "To the man with only a hammer, every problem looks like a nail." Munger believed that to be a successful investor, one needed to understand how the world works, not just how the stock market works.

Munger developed a concept he called the "Latticework of Mental Models." He drew big ideas from physics (critical mass), biology (evolution and adaptation), psychology (cognitive biases), engineering (redundancy and backups), and history. When analyzing a potential investment, Munger didn't just look at the P/E ratio. He looked at the psychological tendencies of the customer base, the biological imperatives of the management team, and the physical constraints of the industry.

Where Buffett would reject a tech stock because he couldn't predict its cash flows (a financial filter), Munger might reject it because he saw a sociological trend that would render the product obsolete (a multidisciplinary filter). Buffett dug deep; Munger went wide. This difference meant that while Buffett provided the depth of analysis required for conviction, Munger provided the breadth of context required for safety.

3. The Optimistic Promoter vs. The Abominable No-Man

Temperamentally, the two men played very different roles in the public and private spheres of Berkshire Hathaway. Warren Buffett is, by nature, a pleaser. He is the optimistic face of capitalism—the grandfatherly figure who believes in the American Tailwind. He enjoys the limelight, the interviews, and the adoration of the shareholders. He is diplomatic, often avoiding direct confrontation or harsh public criticism of specific individuals.

Charlie Munger was the "Abominable No-Man." He was stoic, blunt, and famously curmudgeonly. He did not suffer fools gladly and had zero interest in being liked. While Buffett would gently deflect a foolish question, Munger would eviscerate it with a dry, one-line quip.

This difference extended to their deal-making. Buffett, with his surplus of cash and enthusiasm, was often eager to make a deal. Munger viewed his role as the brakes to Buffett’s engine. He prided himself on saying "no." If Buffett brought ten ideas to Munger, Charlie might shoot down nine of them with brutal efficiency, pointing out risks Buffett’s optimism had glossed over.

Buffett was the gas pedal; Munger was the emergency brake. Buffett was the charismatic leader who rallied the troops; Munger was the cynical sage who ensured they weren't marching off a cliff. This "Good Cop, Bad Cop" dynamic was essential. It allowed Buffett to maintain his benevolent reputation while Munger did the dirty work of killing bad ideas and calling out nonsense.

Part II: The Three Biggest Similarities

Despite their differences in style and intellect, the partnership would have fractured if not for a shared moral and philosophical foundation. These similarities were the glue that held the structure together for sixty years.

1. The Inner Scorecard

Both men lived by what Buffett called an "Inner Scorecard." This concept essentially divides the world into people who care about how they are perceived (Outer Scorecard) and people who care about what they actually are (Inner Scorecard).

Buffett and Munger were remarkably indifferent to public opinion. In the late 1990s, during the dot-com bubble, the entire financial world mocked them. They were called dinosaurs; magazines wrote that "Buffett had lost his touch" because he refused to buy internet stocks. An Outer Scorecard investor would have capitulated, buying tech stocks just to keep up with the S&P 500 and stop the criticism.

Buffett and Munger didn't blink. They knew the math didn't make sense, and they didn't care if they looked foolish in the short term. They shared a profound emotional stability and a commitment to rationality over social proof. They both believed that integrity was not just a moral choice but a financial imperative. "It takes 20 years to build a reputation and five minutes to ruin it," Buffett famously said. Munger echoed this, frequently stating that good ethics is simply good business.

This shared "Inner Scorecard" meant they never had to second-guess each other’s motives. They knew that neither partner would ever cut corners, cook the books, or betray their principles for a quick buck. This trust was the ultimate efficiency mechanism.

2. The Long-Term Horizon (Patience)

In a Wall Street culture obsessed with quarterly earnings and millisecond trading, Buffett and Munger were generational in their timeframe. Both men viewed the stock market not as a casino for trading slips of paper, but as a venue for acquiring partial ownership of businesses.

They shared a disdain for activity for activity’s sake. Munger famously said, "You make money by waiting, not trading." Both were content to sit on billions of dollars of cash for years—sometimes decades—doing absolutely nothing, waiting for the "fat pitch."

This shared capacity for boredom is rare. Most investors feel a psychological need to "do something" to justify their fees or their existence. Buffett and Munger were perfectly happy to read, think, and wait. When they did act, they acted with massive aggression, but they were united in the belief that great opportunities are rare and must be waited for with infinite patience.

This similarity prevented conflict during dry spells. If one partner had been impatient and the other patient, the partnership would have dissolved during the long bull markets where value was scarce. Because both were content to wait, they survived the lean years together.

3. Disdain for the "Institutional Imperative"

"Institutional Imperative" is the tendency for corporate executives to mindlessly imitate their peers—if every other CEO is buying a corporate jet, acquiring a competitor, or using complex derivatives, they must do it too.

Buffett and Munger shared a deep, visceral hatred for this behavior. They loathed the bureaucracy, the bloated fees, the consultants, and the "synergy" buzzwords that plagued corporate America. They ran Berkshire Hathaway with a headquarters staff of roughly 25 people, despite having hundreds of thousands of employees globally. They had no legal department, no HR department, and no public relations department at the parent level.

They both viewed the standard "2 and 20" hedge fund fee structure as highway robbery. They both hated EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization), which Munger derisively called "bullshit earnings." They both viewed derivatives as "financial weapons of mass destruction."

This shared independence of mind meant that Berkshire Hathaway was built as a fortress against stupidity. They didn't structure the company to look like a standard conglomerate; they structured it to make sense to them. They refused to split the stock (until the B shares were forced upon them), they refused to provide earnings guidance, and they refused to schmooze with analysts. They were united in their rebellion against the status quo.

Part III: The Three Biggest Synergies

Synergy is a word Charlie Munger was skeptical of in corporate mergers, but in the case of Buffett and Munger, it was undeniably real. Their combined output was exponentially greater than the sum of their individual capabilities.

1. The Transformation: From Cigar Butts to Franchises (See’s Candies)

The greatest synergy of their partnership was Munger’s successful reprogramming of Buffett’s brain. Left to his own devices, Buffett might have become the richest man in Omaha, flipping cheap stocks and liquidating small companies. He would have been successful, but he would not have built Berkshire Hathaway.

The pivot point was the acquisition of See’s Candies in 1972. See’s was a high-quality California chocolate company trading at a price that was fair, but not "cheap" by Ben Graham’s standards. It was trading at roughly three times book value.

Buffett wanted to walk away. The price was too high. Munger pushed back. He argued that See’s had "pricing power"—a brand loyalty so strong that they could raise prices every year without losing customers. He convinced Buffett that paying a premium for quality was better than buying a dying textile mill for a discount.

Buffett listened. They bought See’s. Over the next few decades, See’s Candies produced roughly $2 billion in pretax earnings, which Buffett used to buy other businesses like Coca-Cola. The lesson of See’s Candies unlocked the strategy that built the empire. Munger provided the qualitative vision; Buffett provided the capital allocation genius to execute it. Without Munger, Buffett misses See’s. Without See’s, there is no Coca-Cola investment. Without Coca-Cola, there is no modern Berkshire.

2. The "Two-Second" Trust System

In the corporate world, a multi-billion dollar acquisition usually involves months of due diligence, armies of lawyers, investment bankers, and slide decks. The synergy between Buffett and Munger allowed them to bypass this entire friction-filled apparatus.

Because they understood each other’s minds so perfectly and respected each other’s differing viewpoints, they could make decisions with terrifying speed. When a deal came to Buffett, he could call Munger and say, "Charlie, what do you think?" Munger would grunt a few sentences, and the decision was made.

They famously bought major companies based on a handshake or a brief phone call. This speed was a massive competitive advantage. Sellers preferred Berkshire because they knew if Warren and Charlie said "yes," the check would clear. There was no board meeting to wait for, no financing contingencies.

This synergy—the ability to deploy billions of dollars with the speed of a startup—was only possible because Munger’s skepticism balanced Buffett’s optimism instantaneously. They were a two-man checks-and-balances system that operated in real-time. This efficiency saved them millions in fees and allowed them to snatch opportunities before competitors could organize their committees.

3. Intellectual Compounding

The final and perhaps most beautiful synergy was their mutual education. They were each other’s best teachers. Buffett taught Munger the nuts and bolts of insurance float and capital allocation. Munger taught Buffett about consumer psychology, competitive moats, and the dangers of cognitive biases.

For sixty years, they engaged in a continuous feedback loop. When Buffett drifted toward a "cigar butt," Munger pulled him back. When Munger got too theoretical, Buffett grounded him in the numbers. They sharpened each other.

This was evident in their foray into BYD, the Chinese electric battery and car manufacturer. This was a quintessential Munger pick—a bet on a brilliant engineer (Wang Chuanfu) and a technological shift (batteries). It was outside Buffett’s traditional circle of competence. But because Munger had expanded Buffett’s horizons, and because Buffett trusted Munger’s "mental models," they made the investment. It became one of their most profitable bets of the 21st century.

They made each other smarter. A solo Warren Buffett stagnates in the 1960s style of investing. A solo Charlie Munger perhaps lacks the singular focus to build a financial fortress. Together, they became a learning machine that adapted to every decade, from the inflation of the 70s to the tech boom of the 2000s.

Conclusion: The Legacy of a Dual Mind

The partnership of Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger is a testament to the power of complementary minds. They proved that 1 + 1 can equal 100 if the components are right.

Their story teaches us that to succeed, we don't need to find someone exactly like us. We need to find someone who shares our values but challenges our methods. We need a partner who sees the world through a different lens—who sees quality where we see expense, who sees risk where we see opportunity, and who has the courage to tell us "no" when we most need to hear it.

Buffett was the eyes, scanning the horizon for opportunities. Munger was the glasses, sharpening the focus and filtering out the illusions. As Munger passed away in late 2023, the era ended, but the lesson remains: Greatness is rarely a solo endeavor. It is the result of synergy, patience, and the wisdom to listen to a partner who knows better.