In the lexicon of modern self-improvement, we talk endlessly about habits, systems, productivity hacks, and goal setting. We obsess over the "what" and the "how" of success. Yet, we rarely pause to scrutinize the "who."

From the moment we are born, we learn not by reading manuals, but by watching others. This mechanism does not shut off when we turn eighteen. Throughout our lives, we are unconsciously shaping ourselves in the image of the people we admire. We are constantly downloading the software of our heroes' minds—their values, their heuristics, their temperaments—and running it on our own hardware.

This makes the selection of heroes a high-stakes game. If you choose the wrong heroes, you may inherit their blind spots along with their strengths. You may climb a ladder only to realize it was leaning against the wrong wall. But if you choose the right heroes—as Charlie Munger chose Benjamin Franklin, or as Steve Jobs chose Edwin Land—you acquire a navigational chart for life that has already been stress-tested by greatness.

Picking a hero is not an act of fandom; it is an act of architectural planning for your own character.

Part I: The Physics of Influence

To understand why hero selection matters, we must first understand the mechanism of influence. We often believe we are rational agents making independent choices, but sociology and psychology suggest otherwise. We are permeable vessels, constantly absorbing the emotions, standards, and ambitions of those we pay attention to.

The Mirror Neuron Effect

Neuroscience tells us about mirror neurons—cells in the brain that fire not only when we perform an action, but when we observe someone else performing it. When you watch a master craftsman work, or listen to a philosopher argue, your brain is, in a very real sense, rehearsing those actions.

If your heroes are impulsive, loud, and prone to shortcuts, your neural pathways begin to normalize that behavior. If your heroes are thoughtful, disciplined, and rigorous, you effectively "practice" those traits simply by observing and studying them. By curating your heroes, you are curating the inputs that train your neural networks.

The Munger Concept: "The Eminent Dead"

Charlie Munger, the late vice chairman of Berkshire Hathaway and one of the most lucid thinkers of the last century, understood this better than anyone. Munger did not rely solely on living mentors. He believed that the living were too scarce in number and lacked the excellence to serve as a complete board of advisors.

Instead, Munger cultivated what he called a friendship with "the eminent dead." He spent his life reading biographies, dissecting the lives of the great figures of history to understand what worked and what didn't. His primary hero was Benjamin Franklin.

Why Franklin? Because Franklin was the archetype of the "autodidact"—the self-taught man who improved himself through rigorous introspection and systematic habit formation. Munger didn't just admire Franklin; he used Franklin. When Munger faced a complex problem or a moral dilemma, he could run a simulation: "What would Old Ben do?"

This is the utility of a dead hero. They cannot disappoint you with a new scandal. Their lives are complete data sets. You can see the beginning, the middle, and the end. You can see how their early decisions compounded over forty or fifty years. You can judge the tree by the fruit it bore at the very end of the season.

Part II: The Case Studies of Greatness

History is littered with successful people who stood on the shoulders of specific giants. By analyzing these relationships, we can see that they didn't just hang posters on their walls; they internalized the specific mental models of their idols.

Steve Jobs and Edwin Land

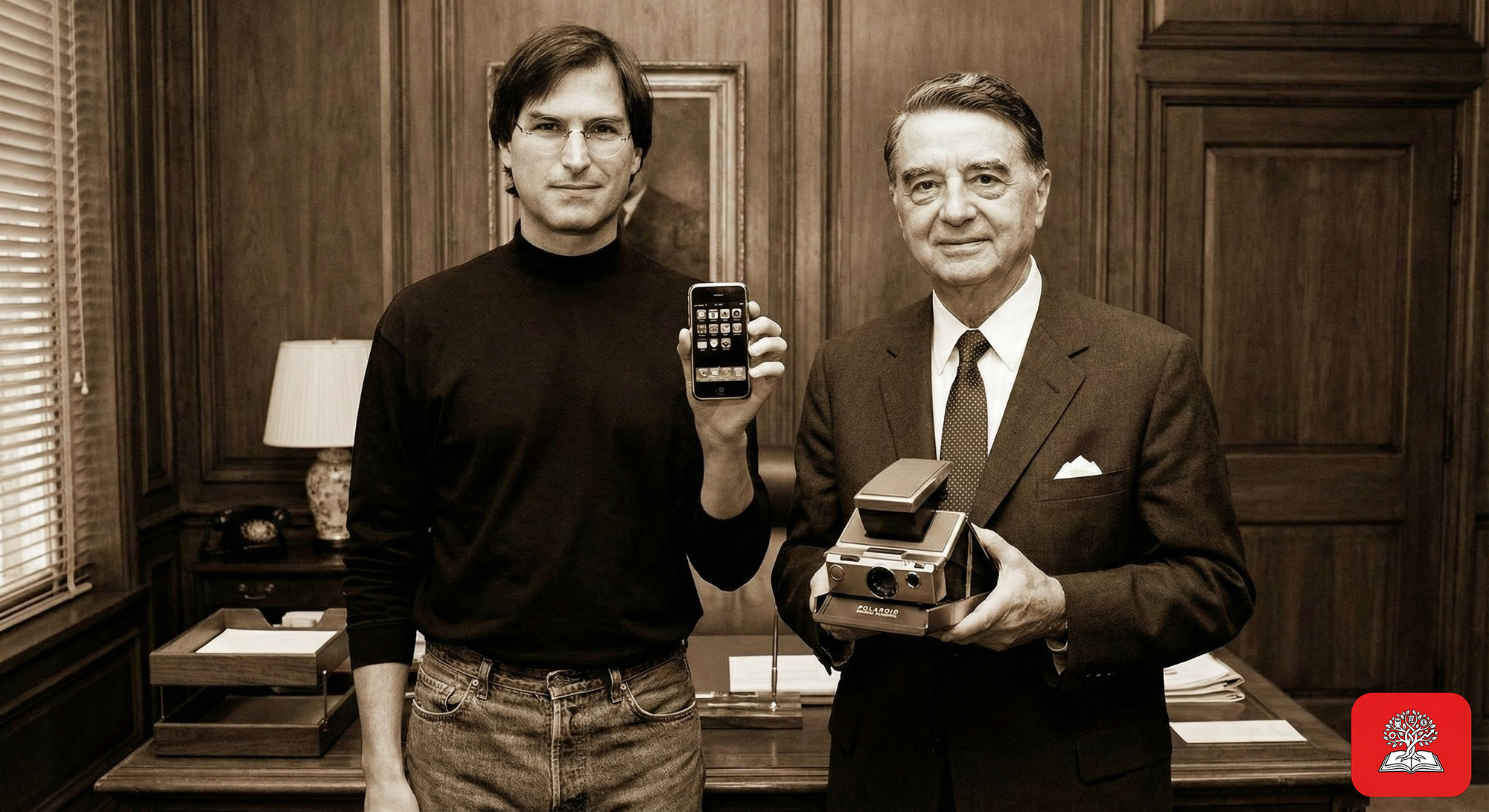

Steve Jobs is often cited as a singular genius, a man who invented the future out of thin air. But Jobs himself was open about his hero: Edwin Land, the founder of Polaroid.

Edwin Land was not just an inventor; he was a scientist who understood the importance of humanity. Land famously said his goal was to stand at the intersection of "arts and science." He believed that a product shouldn't just be functional; it should be magical. He believed in the "reveal"—the moment a Polaroid photo developed in your hand was a piece of theater, not just chemistry.

Jobs absorbed this completely. The launch of the iPhone, the design of the Mac, the obsession with packaging—these were all echoes of Land’s philosophy. Jobs didn't copy Land’s specific inventions; he copied Land’s taste. He copied the lens through which Land saw the world.

This is a critical distinction in hero selection: Do not look for people to mimic; look for perspectives to adopt. Jobs chose a hero who valued aesthetics as much as engineering. Had he chosen a hero who valued only cost-cutting, like a typical 1980s CEO, Apple as we know it would not exist.

Warren Buffett and the Hybrid Model

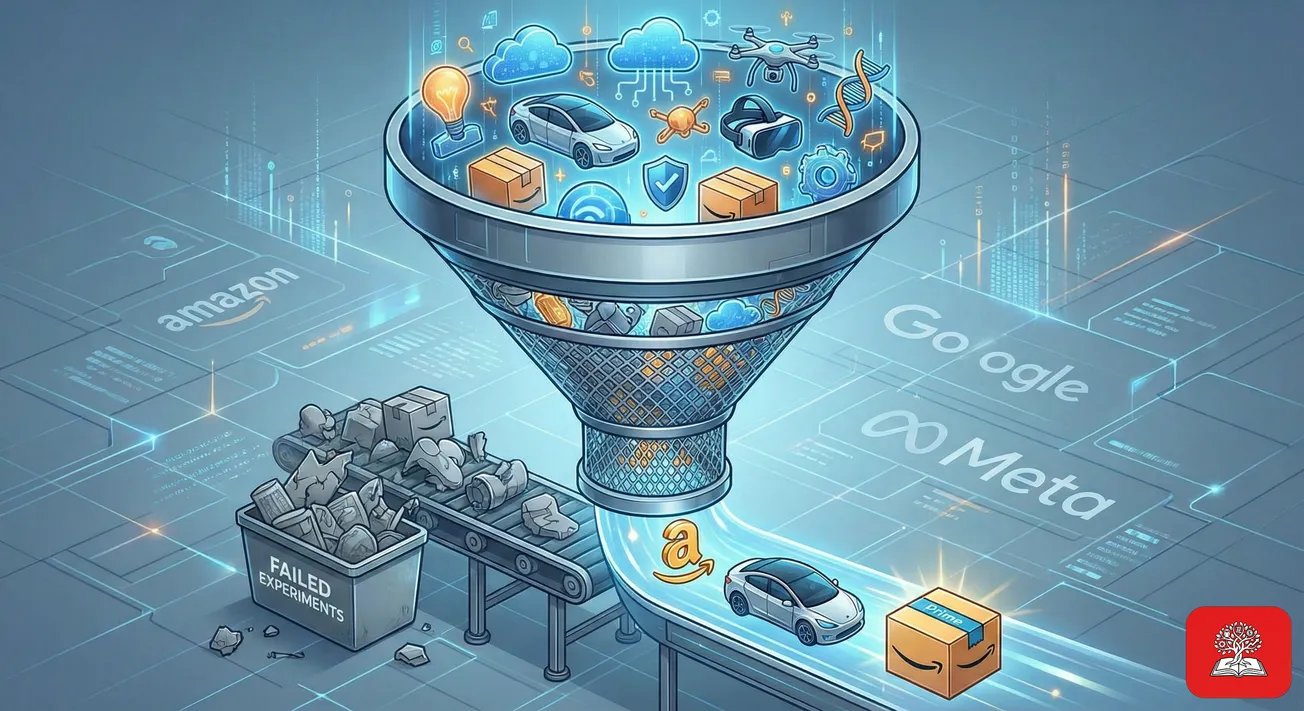

Warren Buffett offers a masterclass in the evolution of hero worship. Early in his career, Buffett was a devout disciple of Benjamin Graham, the father of value investing. Graham’s philosophy was simple: buy cheap, cigar-butt stocks that have one puff left in them. It was a mathematical, risk-averse approach.

Buffett followed this religiously and made a fortune. But he eventually hit a ceiling. The strategy didn't scale, and it didn't account for the quality of the business.

Enter Charlie Munger and the influence of Philip Fisher. Fisher believed in buying great companies and holding them forever—a qualitative approach. Buffett had to mentally synthesize his original hero (Graham) with a new influence (Fisher). He famously stated he became "85% Graham and 15% Fisher."

This highlights an advanced strategy: The Composite Hero. You are not obligated to worship at the altar of one person. You can take the discipline of a Navy SEAL, the compassion of Mother Teresa, and the investing acumen of Warren Buffett. You can piece these disparate qualities together to create a mosaic of ideal character traits that serves your specific purpose.

Part III: The Traps of Hero Selection

Not all heroes are created equal. In the age of social media, we are bombarded with potential idols—influencers, tech moguls, athletes, and politicians. The signal-to-noise ratio is terrible. Most people fall into specific traps when choosing who to admire.

Trap 1: The Halo Effect

The Halo Effect is a cognitive bias where we assume that because a person is good at one thing (making money, singing, playing basketball), they are good at everything (politics, morality, health advice).

We see a billionaire tech founder and assume they must also be a great father, a wise philosopher, and a beacon of health. Often, the opposite is true. Many people who achieve extreme outliers of success do so by sacrificing every other aspect of their lives. If you idolize a tycoon for their wealth, be careful you don't also accidentally download their broken family life or their nervous breakdown.

The Fix: Be specific about what you are admiring. "I admire this person’s work ethic, but I reject their treatment of employees." Segment the hero.

Trap 2: Admiring the Outcome, Not the Process

It is easy to admire the person standing on the podium holding the gold medal. It is much harder to admire the person waking up at 4:00 AM for four years to train in the dark.

When we pick heroes based on their "highlight reels" (Instagram feeds, magazine covers), we are setting ourselves up for failure. We crave the result without respecting the cost.

The Fix: Pick heroes who have documented their struggle. Read the biographies that detail the "wilderness years." Churchill during his political exile. Lincoln during his bouts of depression. Jobs after he was fired from Apple. A true hero teaches you how to endure suffering, not just how to celebrate victory.

Trap 3: The Aesthetic of Success vs. The Mechanics of Success

In the modern business world, there is a cult of "hustle porn." We admire people who look busy, who post photos of private jets, who speak in confident aphorisms. We confuse the aesthetic of success with the mechanics of competence.

Real competence is often quiet. It is often boring. The greatest investors spend all day reading annual reports, not tweeting. The greatest writers spend hours staring at blank walls, not attending galas. If your heroes are loud, you will learn to be loud. If your heroes are deep, you will learn to be deep.

Part IV: A Framework for Choosing Your "Personal Board of Directors"

How do you practically select the right heroes? You should view this as hiring a "Personal Board of Directors." These are the people you will mentally consult when you face a crisis. You should vet them as rigorously as a company vets its board members.

Here is a four-point framework for hero selection.

1. Values Alignment

Before you look outward, you must look inward. What do you actually value? If you value tranquility and family, do not choose a hero who worked 100 hours a week and died of a heart attack at 50, no matter how rich they were.

There must be a fundamental resonance between your desired destination and their path. If you want to be a great writer, studying a financier may secure your retirement, but it will never nourish the creative spirit required for great writing.

2. The "Newspaper Test" Integrity

Warren Buffett suggests living your life as if your actions were to be printed on the front page of the local newspaper the next day, written by a smart but unfriendly reporter.

Apply this to your heroes. If the private life of your hero was exposed, would you still admire them? While we can separate art from the artist to some degree, for a hero—someone you model your character after—integrity is non-negotiable. Look for people who were the same in the dark as they were in the light.

3. Resilience Over Perfection

Do not look for perfect people. They do not exist. Instead, look for people who possessed "Anti-Fragility." Look for heroes who made mistakes, admitted them, and came back stronger.

We learn more from a hero’s recovery than from their perfection. Washington’s ability to retreat and keep his army together is more instructive than Alexander the Great’s endless winning streak. The former teaches resilience; the latter teaches hubris.

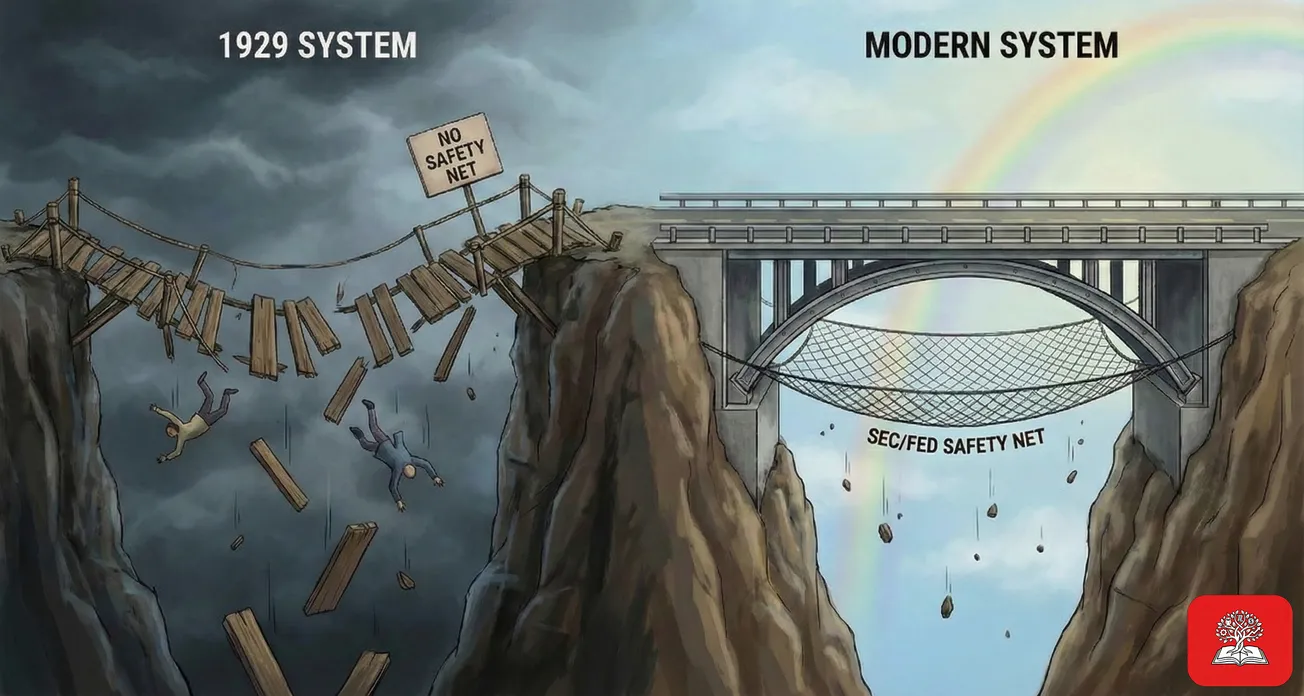

4. Deep Time (The Lindy Effect)

The Lindy Effect is a concept suggesting that the future life expectancy of some non-perishable things (like a book or an idea) is proportional to their current age. Ideas that have survived 2,000 years are likely to survive 2,000 more.

Apply this to heroes. The trendy CEO on the cover of Forbes might be indicted for fraud next year. But Marcus Aurelius? He has stood the test of 1,800 years. His wisdom is "Lindy." Prioritize heroes who have stood the test of time. Their lessons are universal, not situational.

Part V: How to "Consume" Your Heroes

Once you have identified your heroes—perhaps a mix of Franklin, Curie, King, and a grandparent—how do you actually utilize them? Passive admiration is useless. You need active engagement.

1. Deep Immersion (The "Deep Dive")

Do not just read a Wikipedia summary. If you pick Winston Churchill, read the massive biographies. Read his own writings. Watch his speeches. You want to understand the texture of his mind.

David Senra, host of the Founders podcast, advocates for reading every book ever written about your hero. When you do this, you start to spot the patterns. You see the inconsistencies. You move from a cartoonish understanding to a nuanced 3D model of the person.

2. Reverse Engineering

Take a decision your hero made and work backward. Why did Bezos leave a high-paying job at D.E. Shaw to sell books on the internet? It wasn't a whim. It was his "Regret Minimization Framework."

When you reverse engineer the decision, you uncover the mental model.

- Hero: Jeff Bezos.

- Action: Quit stable job for risky startup.

- Mental Model: "In 40 years, will I regret not trying this?"

- Application: Use that question for your own career choices.

3. The Counterfactual Simulation

This is the ultimate practical application. When you are angry, fearful, or confused, pause and ask: "What would my heroes do?"

This sounds cliché, but it is a powerful psychological tool. It forces you to disassociate from your immediate emotional state and view the problem through a different lens—a lens you respect.

If you are angry at a slight, and your hero is Lincoln, you remember Lincoln's "hot letters." He would write a furious letter to the person who wronged him, and then put it in a drawer and never send it. By asking "What would Lincoln do?", you save yourself from burning a bridge.

4. Copying to Innovate

Kobe Bryant, the legendary "Black Mamba," spent his early years obsessively studying Michael Jordan’s game frame by frame. He didn't just watch the highlights; he mimicked the footwork, the shoulder fakes, and the iconic fadeaway jumper until the mechanics were etched into his muscle memory. He wanted to feel the exact rhythm of a champion flowing through his own body.

He didn't become Michael Jordan. He became Kobe Bryant. But he built his unique "Mamba Mentality" on the foundational rhythms of his hero. By "typing out" Jordan's moves with his own feet, he internalized a standard of excellence that most players never even perceive.

Copy your heroes’ habits until they become your own. Copy their reading lists. Copy their work routines. Eventually, you will naturally deviate and find your own voice, but you will be deviating from a base of quality.

Part VI: The Danger of "Never Meeting Your Heroes"

There is an old saying: "Never meet your heroes." It implies that proximity breeds disappointment. Real people have bad breath, bad moods, and petty grievances.

But this saying misses the point. The goal of a hero is not to find a god to worship; it is to find a standard to aspire to. In fact, realizing your hero is flawed is a crucial step in your own development.

When you realize that Benjamin Franklin was vain, or that Steve Jobs was cruel, or that Kobe Bryant was abrasive, it humanizes the achievement. It stops being "magic" and starts being "effort."

If your heroes were perfect gods, you could never emulate them. You would have an excuse: "Well, they were born perfect; I am just a human." But when you see their flaws, and see that they achieved greatness despite those flaws, it removes your excuse. It means greatness is accessible to the flawed—which includes you.

The Evolution of Heroes

As you grow, your heroes should change. The heroes of your twenties—perhaps rebels, risk-takers, and iconoclasts—may not serve you in your forties, when you might need heroes of stewardship, patience, and wisdom.

It is healthy to outgrow a hero. It means you have learned the lesson they had to teach, and you are ready for the next curriculum. Do not cling to a hero out of nostalgia. If you are no longer learning from them, thank them for their service and look for a new guide.

Part VII: Becoming the Hero

The final stage of this process is the transition from apprentice to master. There comes a time when you must stop looking solely backward at the dead, and start looking forward at those watching you.

Whether you like it or not, you are likely a hero to someone. A child, a junior employee, a sibling, a friend. They are watching you with the same desire to imitate that you once felt for your heroes. They are downloading your software.

This is the ultimate accountability mechanism. Live your life in a way that, if someone were to pick you as their hero, you would be comfortable with the outcome.

The Legacy of Character

Charlie Munger did not just admire Ben Franklin; he eventually became a figure who sits on the same shelf as Franklin. Young investors today ask, "What would Charlie do?"

This is the cycle of civilization. We stand on the shoulders of giants, not just to see further, but so that one day, we can become the shoulders for the next generation.

Conclusion

We live in a world that emphasizes the "self-made." We love the myth of the lone genius. But the "self-made" man is a lie. We are all collages of our influences. We are all patches of the people we have loved and admired, stitched together by our own unique experiences.

To leave this to chance is to gamble with your destiny. To be passive about your heroes is to let the currents of social consensus decide who you become.

Be ruthless in your selection. Be rigorous in your study. Be active in your emulation.

Find the people who have lived the life you want to live. Study them until they feel like friends. Let their wisdom seep into your bones. And then, when you are ready, put the biography down, step out into the arena, and act.

References

This article is a synthesis of ideas from several great thinkers. If you want to go deeper into the concepts of hero selection and mental models, take a look at these references:

- Podcast: "Founders" by David Senra (link)

- Book: "Antifragile" by Nassim Nicholas Taleb. (link)

- Book: "The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin" by Benjamin Franklin (link)

- Book: "Steve Jobs" by Walter Isaacson (link)

- Book: "The Snowball" by Alice Schroeder (link)

- Book: "Poor Charlie’s Almanack" by Charlie Munger and Peter Kaufman (link)

- Book: "Common Stocks and Uncommon Profits" by Philip Fisher (link)